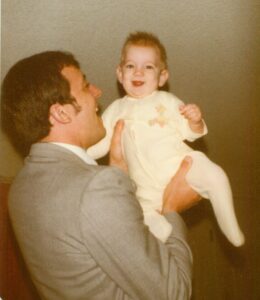

Soon after we had our third baby, something unexpected happened that led to some of the most traumatic times we ever experienced as a family. It was 1981 and we had recently moved to California. While we were on vacation, still recovering from the move and having a baby, we found our four-week-old baby unresponsive. We rushed him to the nearest hospital, but it took 15-20 minutes to get there. We tried to give him mouth-to-mouth, but it turned out his heart was not even pumping, so it had no real effect. Once at the hospital, a team of doctors, nurses and a defibrillator went to work. Finally, a nurse came out in tears and told us, “We have just seen a miracle in here.” They had resuscitated him. He was alive, but just barely. It had been 45 minutes between when we had found him and when they were able to restart his heart—way too long without oxygen for a happy outcome.

Soon after we had our third baby, something unexpected happened that led to some of the most traumatic times we ever experienced as a family. It was 1981 and we had recently moved to California. While we were on vacation, still recovering from the move and having a baby, we found our four-week-old baby unresponsive. We rushed him to the nearest hospital, but it took 15-20 minutes to get there. We tried to give him mouth-to-mouth, but it turned out his heart was not even pumping, so it had no real effect. Once at the hospital, a team of doctors, nurses and a defibrillator went to work. Finally, a nurse came out in tears and told us, “We have just seen a miracle in here.” They had resuscitated him. He was alive, but just barely. It had been 45 minutes between when we had found him and when they were able to restart his heart—way too long without oxygen for a happy outcome.

Our baby was life-flighted to a children’s hospital 5 hours away. We followed in our car the next day to find him in intensive care, still unconscious and on life support. Technology was not what it is now and the doctors had no way to determine the cause of his heart problem, or the severity of the damage, but they told us the prognosis was not good. After three days of agonizing anticipation, we went into the ICU to visit our baby. He opened his eyes and we knew we had our baby back—at least for the time being. However, they could not get his heart into a normal sinus rhythm and he was still on a breathing machine, feeding tube and wired up to several machines.

Our baby spent two weeks in intensive care. The doctors consulted with every specialist there was and even discussed sending him to Houston where there were more tests they could run. Again, pediatric cardiology was far less advanced back then, and they finally determined it was not worth the risk of sending him to Houston. Our baby was lying in the crib, his hands wrapped and pinned to the mattress so he would not accidentally pull out tubes. You could tell he was crying, but because of the ventilator, you could not hear any sound come out. We could not pick him up to comfort him. It was heart-breaking.

At the end of those two weeks, the doctors told us there was nothing more they could do for him and that we should take him home and enjoy being with him as long as we could. We asked what the diagnosis was. The head of cardiology looked straight at us and said it was a syndrome unique to our son. “We have never seen this before and we hope never to see it again.” We returned to California, and at the doctor’s recommendation, checked our baby into the California hospital. The Utah doctors had contacted the California doctors, so they knew our baby was coming, but they were not prepared for what they saw. Those were the blackest weeks of our life. We were torn between trying to care for two toddlers at home and spending as much time as we could at the hospital. Things dragged on and on with no answers. Finally, after three more weeks in the hospital, the California doctors came to the same conclusion—they had no idea of the cause, no idea of why he was still alive given his erratic heart arrythmias and no idea what the prognosis was for the future.

We took our baby home and tried to do our best at getting back to normal life. They did not send him home with a heart monitor because his heart was so erratic that the monitor would have constantly gone off. We purchased a stethoscope which we used to see if his heart was regular enough that we felt comfortable putting him down in his crib for bed. We developed a routine where we would take turns in the morning checking on him. One day I would go in to see if he was still alive and the next day his dad would go in. Occasionally, when his heart was so bad that we could only count 25 or 30 erratic beats a minute, we would drive the half hour into the emergency room, where they would confirm the irregularities and send us home hours later with no answers. By the time he was two years old, trips to the emergency room became way less frequent and his heart became much more regular.

We took our baby home and tried to do our best at getting back to normal life. They did not send him home with a heart monitor because his heart was so erratic that the monitor would have constantly gone off. We purchased a stethoscope which we used to see if his heart was regular enough that we felt comfortable putting him down in his crib for bed. We developed a routine where we would take turns in the morning checking on him. One day I would go in to see if he was still alive and the next day his dad would go in. Occasionally, when his heart was so bad that we could only count 25 or 30 erratic beats a minute, we would drive the half hour into the emergency room, where they would confirm the irregularities and send us home hours later with no answers. By the time he was two years old, trips to the emergency room became way less frequent and his heart became much more regular.

During those early years, our son definitely did not fit into the same mold as our other children. He was slower in his development and had very poor emotional regulation. He did not talk until he was 3½, so communication was hard. His ability to deal with frustration was low. There were times when he was truly a sweet, tender little child, but there were more moments when we did not know how to deal with him. Although his communication was behind, he appeared to be a very bright child. We came to believe that many of his behavioral problems were related to trauma he experienced as a baby. As an infant, he had not gotten the physical affection and love he needed because of his medical problems, and it seemed some type of attachment disorder had resulted. Furthermore, we realized because we were so uncertain if he would live during the first two years, we subconsciously detached. He got our care, but the normal parent/child connection was lacking. He was increasingly withdrawn and uncooperative. He did not trust anything in life—even us.

Having realized the problem, we made a concentrated effort to break through and connect with our son in a healthy way. We gave him as much love and physical affection as we could. When we could see him withdrawing, we would get down on the floor in front of him and look directly into his eyes. It was months before he could even stand to maintain eye contact. For two more years we concentrated most of our efforts on trying to get through and build a relationship with him. We finally got to the point where he would communicate when he was upset instead of throwing a tantrum. He became a very loving, affectionate child. Although he was still a little slow in his development compared to our other children, he fell within a normal range. By age four, he still had a very difficult time sitting still or behaving in a classroom situation, but we felt good about the progress he was making.

Then he turned five, and we enrolled him in kindergarten. Things went radically downhill from that time on. He had a wonderful, sweet kindergarten teacher who tried everything she could to get him to sit and do his work. Still, his disruptions to the class were so bad that he spent much of the year sitting in the principal’s office. In first grade, things only got worse. He would not do any work. He would not listen or obey. He disrupted the class by doing things like standing up on his chair and singing at the top of his lungs while the teacher was trying to talk. He hit other children. School life rapidly became a nightmare.

The teachers knew that he had severe learning disabilities, and one told me that they thought he was somewhat retarded. I had a hard time believing that given all the things he did that were mentally advanced for his age. After meeting with the teachers and staff, we decided to have him tested for special education placement. It came as quite a shock to the teachers to find that our son had an IQ of 130. Since the tests indicated he should be achieving much more at school than he was, they placed him in resource teaching.

During this time, our pediatrician tried medication for hyperactivity, which was immediately discontinued by his cardiologist because it counteracted his heart medicine. We took our son to a good psychiatrist who, as a last resort, suggested we try an anti-depressant. That did not work either. The psychiatrist indicated that the prognosis for children like our son was not good, especially as he got older, and we could see he was right. We began to feel like we were locked into a hopeless, no-win situation.

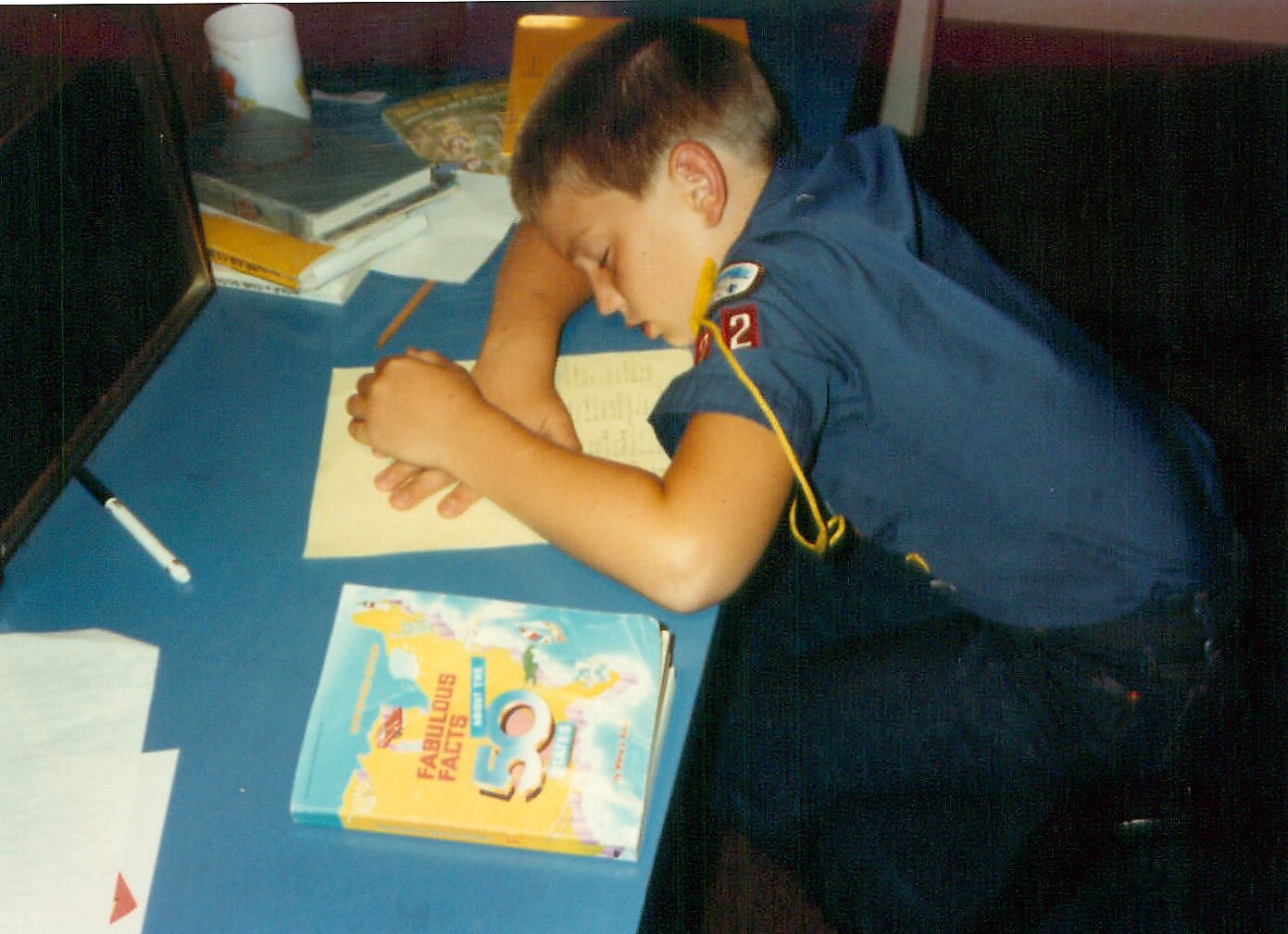

By this time, our son was in a special resource classroom more hours than he was in his regular class. My husband was going to school during his lunch hour to try and help our son get his work finished. His older sister would also come down from fourth grade every day to sit with him and help him stay on task. Despite all these efforts, his work was not getting done. By the time he finished second grade, my son had only made it through 30 pages of a first grade math workbook. I gave up trying to make my son spend all his time after school finishing schoolwork; it only made matters worse. My son’s teacher would send him home with a daily report card with several things on it: “I stayed in my seat. I finished my work. I did not talk out of turn”, etc. If he got all five things marked off, he came home with a “good day” sticker. The reward was that the whole family got to go out to a restaurant of his choice. He only got one “good e day” sticker the whole year. My son was an angry, aggressive, unmanageable child. I was a frustrated, scared, despairing mother.

The final straw came at the end of that school year when our family was at the school awards ceremony. My oldest daughter got the top student award in three subjects for 4th grade. Our older son got the top math student award for 5th grade. At the end of the ceremonies, my younger son had disappeared. I finally found him all by himself, huddled on the stairs by the stage. He was crying. I asked him what the problem was. Between sobs he said, referring to his older siblings, “they do not even try and they get the top student awards in school. I try as hard as I can and only get one ‘good day’ sticker the whole year.” The pain he was going through hit me like a ton of bricks. What must it be like to feel like you were a failure with no hope of success? What must it be like to feel like no matter the effort you put in, you could never meet expectations? How frustrating must it be for people to compare you to other children that do not struggle with the things that you do?

That week we committed to pulling our son out of public school. It was clear he had learning disabilities, particularly when it came to reading and writing. Additionally, he could not even sit still long enough to do anything. I was at a loss as to what to do with him though. One day as I was agonizing over how to deal with the frustration I felt every time I tried to get my son to sit and do schoolwork, I heard in my mind: “Do you remember how much happier he was back when he was four years old? He needs to go back to that point in his life and start over!” That sounded easy enough until I stopped to think about it. He was now in third grade. Third graders do a lot of work. They read very well. They can write nice reports. What would people think if I did not make my son do all those things? Then another answer came: “You cannot make your son do anything, but you can help him start wanting to learn.”

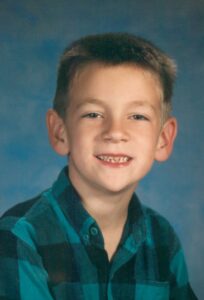

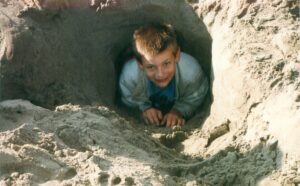

I was a school teacher by trade and racked my brain to remember anything that might cast some light on how to proceed. Slowly, pieces started to fit together, and real progress, as invisible as it might have been to the outside world, began. I decided to let my son “start over” and essentially go back to being four. I found “unschooling” was the answer for my son. We turned screens off and filled the house with fun, enticing things to keep a little boy busy. To this day when someone asks what my son did for school during those early years, everyone in the family replies, “He spent his time in the back yard digging holes”. That is not too far from the truth. School looked like Legos, craft projects, bike riding, making airplanes and building forts.

You may ask, was I comfortable with that? No, not at the time. I just could not find any other alternatives. It was pretty scarry when my son started 5th grade (age wise…there were no grade levels by this point in our home schooling) and he still did not know what multiplication was. The peer pressure on me would have been too great had it not been for the fact that our close friends knew what we were dealing with and others outside our family could see the progress our older kids were making in school, so they gave us the benefit of the doubt.

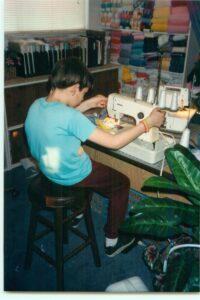

My son finally started his first math book when he was 12, jumping straight into Saxon math. I do not recommend this for mos t children, but I want to be honest and tell it like it really was. He was fourteen when he wrote his first short paper. His total reading experience consisted of science encyclopedias and family scripture time. By the time he was sixteen he decided that sitting for hours on end trying to focus on Saxon Math was not going to work for him, so he enrolled himself at the junior college and took Algebra II/Trig. By the time he left home to go to college at eighteen, he was ready to enroll in college Calculus and Physics. He graduated with his BS in computer science in four years and has since worked as a computer programmer.

t children, but I want to be honest and tell it like it really was. He was fourteen when he wrote his first short paper. His total reading experience consisted of science encyclopedias and family scripture time. By the time he was sixteen he decided that sitting for hours on end trying to focus on Saxon Math was not going to work for him, so he enrolled himself at the junior college and took Algebra II/Trig. By the time he left home to go to college at eighteen, he was ready to enroll in college Calculus and Physics. He graduated with his BS in computer science in four years and has since worked as a computer programmer.

So what about all those disabilities he had? They seemed to fall away one at a time. Sometimes I wonder if they ever even existed, or if what I really saw falling away was my preconceived notions of how a child ought to think, act and feel. Sometimes I am amazed that my son was ever labeled as having disabilities, especially after reading the dictionary definition: “Deprived of ability or power; crippled.” So far, I have not found anything that my son has been deprived of the ability or power to do. When given the space, time and security of growing at his own pace, he has been able to do almost everything.

So, what about “Crippled”? I do have to say that my son used to be crippled. But it was his spirit that was crippled, not his mind or his body. Trying to make a child fit into somebody else’s preconceived mold will cripple them. It does not take long before a child realizes they cannot learn at the rate you are arbitrarily prescribing and they give up trying. As time passed, my son became happier and more confident. He forgot he was ever considered a failure. He learned more about himself, what he could do, and how to problem solve through the things that were hard for him.

I learned through our experience that every child is a gifted child. Every human being has a unique set of abilities and strengths. Along with that, they have things that do not come so easily, but that does not constitute a disability that has to cripple them. It merely means there is room for growth. Love, faith, patience, persistence, and a liberal sprinkling of inspiration can go a long way in overcoming all that and helping them to live a happy, successful life.

RELATED ARTICLES

Is there something you would like help or more information on? Submit your questions here.

Do you have a parent help article that you want Simply Smart to consider publishing? Share by clicking here.

- Date Added: January 1, 2024